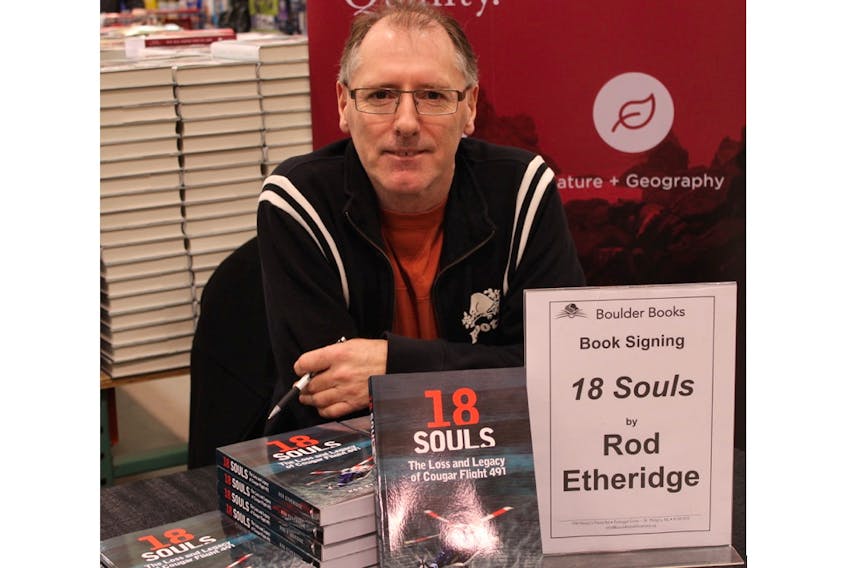

Rod Etheridge’s book, “18 Souls: The Loss and Legacy of Cougar Flight 491” brings the reader through what it was like for families and loved ones to see a typical day turn into horrific loss.

And in the aftermath of that loss, the 17 who died in the crash are remembered a decade later with heartbreaking detail, their legacies marked in ways that include scholarships and parks, but never out of the hearts and minds of their loved ones.

With exceptional grace and respect, Etheridge, a senior producer at CBC N.L., crafts their stories — as well as that of lone survivor Robert Decker, told through his testimony at the public inquiry into the March 12, 2009, crash of Cougar Helicopters Flight 491.

The Telegram sat down with Etheridge for a Q and A about his book.

Q: Rod, how did the book come about?

Etheridge: It was two years ago, the eighth anniversary of the Cougar crash, and I was watching CBC coverage, NTV coverage, The Telegram — all the media coverage — and I noticed that it would be an obligatory line that 17 people died and (there was) one survivor. But it didn’t go on to name the 17 or talk about them. There was maybe a 10- or 20-second clip from one family member at the fence, which is the makeshift memorial. I thought, wow, we don’t even talk about who died.’ And that struck me. … I looked up all their names and thought I would love to tell a story about their lives, how they ended up at the airport that day.

Q: It took two years to put together?

Etheridge: The first six to eight months were just talking to people, and then I started writing and then I found I would go back to people. In the beginning we talked a lot by email because they weren’t ready to be face to face. They would say, “I can’t go there, I am not ready to talk about this yet.” And we would talk by email and messenger, and sooner or later they would invite me to their home, and I would go and sit down for two or three hours and, in some cases, I went and spent the whole day with the family. … When you spend that long with the family, they start to really give you details about the person.

Q: Was it overwhelming once you sat down to start writing?

Etheridge: It was. I knew off the top I wanted to call it “The Loss and Legacy” because I realized early on there was so much in their names — the community park, hockey scholarships, fund-raisers, music scholarships, nursing scholarships — so I knew the legacy was a big part of it. That’s what it was all about in the beginning, the legacy — who they were and how their family and friends remember them.

And then the loss … quite a few of them found out about the crash through the media. Many of them found out with a phone call. They’re sitting down having their breakfast and the phone rang. To me, the loss and the legacy was what it was all about. They were all going about their regular life that day, saying goodbye at the airport or going on to work or getting the kids ready for school. And then a couple hours later the phone rang.

I can’t imagine about those who first heard it in the media.

Q: Did you have a moment where you thought this was too big a project to take on?

Etheridge: I did early on, and I would reach out to people and they would show interest in it. They would say, “This is going to be hard to talk about. I will call you in a couple of weeks,” or, “I will call you in a couple of months.” And I would wait and there would be no reply and then I would write back and say, “Hey I was wondering how you were doing; would you like to talk?” And they would say, “Yeah, I’ll call you tomorrow.” And I’d get no call back tomorrow. And one day I said to my wife, “You know what, I can’t do this. I can’t cause people pain, so I’m just going to drop it.” … I wrote one of the widows, and said, “I just want to let you know if this is too hard, you don’t have to return my phone call. We don’t have to talk about it and we’ll just forget the whole idea.” That was Lori Chynn, John Pelley’s wife, and she wrote me back right away and said, “Rod, I really want to talk to you. But it’s so hard to go back to that day. It's taken me awhile, but I do want to talk to you.” She said she would call me (the next) night. … We were on the phone for three hours. … It was about them telling their story when they were ready. And there were a lot of people who said, “I want to talk to you,” and never did talk to me because they just couldn’t bring themselves to do it.

Q: What struck you about their lives?

Etheridge: The number of people who still go to the graveyard every day. I went to Fortune to visit Burch Nash’s parents — Marjorie and Harold. They are in their 80s now. They get up every morning and have breakfast and drive to the cemetery. They fix up around the headstone and kiss his picture on the headstone and they get in the car and they drive to the park in his name. And they sit there on the benches and they just sit there for an hour. And then they go home and have their lunch and they get in the car and go back to the cemetery after lunch and they go to the park. And in the evening before they go to bed, they get in the car and drive to the graveyard. And they say their day is not complete if they don’t do it. When you see that, you think, that’s what this crash did to some people in this province. It makes you realize the impact.

Q: Is there a life lesson you took from writing this book?

Etheridge: I did take something out of it professionally because I work in the media. Being in a newsroom, there are people calling all the time, there’s a scanner going, you’re always hearing about emergencies, whether how real they are or not and you check it out. You hear about car accidents — get a camera and head out to the Outer Ring Road because there’s an accident. It makes me stop and think, someone is getting a phone call. So, there’s no rush to get that picture up right away. Let’s stop and think about it. So professionally, it makes me take a little more time to do my job because I know while you’re reporting on the disaster or emergency, there’s someone out there getting a phone call. Personally, I knew none of these people in life, but I feel like I know them in death. Some people I could almost hear their voice when a loved one was saying (how they would talk.) I spent so much time with the families, I felt I knew them.

Q: Tell me about the reaction to the book.

Etheridge: When you are writing a book and you are staring at a computer every night, you say to yourself, “I wonder if anyone will read this?” Obviously, friends and family will read it. But I’ve been just overwhelmed by the reaction. So many people have commented that this is a book they want to read. You say, “Did you know anyone?” They say, “No, but I remember where I was that day and I want to read it.” The publisher (Boulder Books) tells me that they’re getting calls every day from stores wanting to put it on their shelves. The other thing is on our doorstep — there’s an offshore industry and I didn’t realize what a community is out there. They work three weeks on/three weeks off, and six months of the year they are on a rig of 400 and 500 people. They all know each other, and they knew those who died. They are still going to the rig every three weeks to support their family.

… It didn’t matter to me if I sold a lot or not, it’s a story I wanted to tell. I’m happy about the reaction because it reinforces it’s something people want to read and know about.

The reason I put 18 souls in front of it is because I went through the tapes of what happened that morning between the air traffic controller and the planes out searching and at one point one person said, “How many people onboard?” and the reply was, “18 souls onboard.”

Q: What’s an example of a detail that touched you?

Etheridge: There was a guy onboard the helicopter called Ken McRae. He was from Nova Scotia and he didn’t work in the offshore. … His daughter was 14 years old (at the time of the crash) and her name is Michelle. … When all her friends would say, “Why are you going to university in Newfoundland?” she would say tuition is really cheap here. She didn’t tell them the truth, that she wanted to live near where her dad died. She got a job at the Spa at the Monastery. … In March she went and asked her boss, “Can I get Sunday the 12th off? I have to go to a memorial.” And her boss said, “Why are you going to a memorial service?” She told her the truth and her boss said (another employee’s) dad was on the same helicopter. Her coworker who she worked with several days a week since September was Allison Nash, Burch Nash’s daughter. They did not know each other’s father was on the helicopter. And they had a cry and a hug. … Michelle has a sister, Alyssa. When the crash happened, Alyssa was in Ottawa. She worked in a coffee shop and she was studying HR with an emphasis on safety in the workplace. A couple years after the crash — few people knew about her connection to it — her bosses said to her, “We’re bringing in all the managers for a safety in the workplace conference. Would you speak, because we know what your specialty is.” She chose Cougar 491 as her case. She got up and spoke and said, “Here are the financial impacts of the crash, here is the workforce impact of the crash and the last one is, here is the personal impact of the crash,” and she put up a photo on the screen of her dad. … Not a person in the room spoke as she told the story of her dad. When it was over, all these managers came up and said, “Thank you so much, we now get it about safety in the workplace and what it means to take care of your employees.”