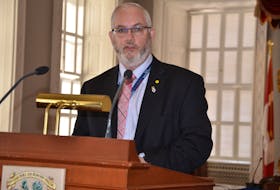

NEW MINAS, NS - May 30, 1993 is a day Tom Bourgeois will never forget.

It was Apple Blossom Festival weekend in the Valley when he received a phone call asking him if he was ready to receive a new lease on life.

Bourgeois had been on peritoneal (home) dialysis for about two years when he received that call. The family jumped at the opportunity to receive a new kidney — and with the transplant, a chance for a prolonged life.

“There were four of us that were called in that same night,” said Bourgeois.

Two people received kidneys, one received a heart, another received a liver.

“The other guy that got the other kidney was just down the hall from me. We met. He was from New Brunswick.”

Bourgeois was able to lead a healthy life following the transplant. He retired as the assistant produce manager from the New Minas Superstore after a 35-year career with Loblaws.

Bourgeois' kidney lasted nearly 25 years before it became evident it was no longer functioning. He's now on hemodialysis and travels to Berwick three times a week for treatment.

'Very stressful'

Prior to Christmas, Bourgeois had to travel to Halifax for the life-preserving treatment.

“It's very emotional; very stressful. It takes a whole day,” said Bourgeois of his treatments.

Each session lasts about four hours, and when he gets home, he's exhausted. Since being transferred to Berwick, it has eased the financial toll on the family as well as the mental anguish of having to drive more than an hour in all kinds of weather.

“I don't think they have a clue what it does to the people,” said his wife of 50 years, Carol Bourgeois.

“When he comes home, he's done for the day. It just tires him out.”

She drove her husband to Halifax for treatment during the wintertime and she described the trips as 'terrible.'

“It certainly is a burden every which way, especially in the winter,” she said. “We were travelling in the winter and worried about storms.”

The family is eagerly awaiting the opening of the satellite dialysis unit at the Valley Regional Hospital in Kentville. The 12-station dialysis unit will replace the six-station facility at the Western Kings Memorial Health Center in Berwick. Construction is slated to begin this summer.

While the news will mean Bourgeois has less of a drive to receive his treatment, he can't stress enough the importance of organ donation.

“Put it in big bold letters: please sign your donor card. That's my wish,” he said, noting he doesn't medically qualify for another kidney.

READ ABOUT PLANS FOR A SATELITE DIALYSIS UNIT AT VALLEY REGIONAL HOSPITAL HERE.

READ ABOUT A HANTS COUNTY DIALYSIS PATIENT LONGING FOR TREATMENT CLOSER TO HOME.

A silent disease

Kerry MacIvor, the development co-ordinator with the Kidney Foundation of Canada – Atlantic Branch, said kidney disease is often considered a silent disease.

“A lot of times, many people don't actually realize that they have kidney disease until it's too late, and then shortly after that, they do need to start some sort of a treatment — whether it be dialysis or a work up onto a transplant list,” said MacIvor.

With statistics showing the number of people awaiting transplants, MacIvor said there is a need for people to sign up to donate their organs.

In 2017, 16 people in Nova Scotia donated a kidney — 15 of which came from cadavers — and 23 Nova Scotians received a kidney transplant. Twenty-one New Brunswickers and 16 people from Newfoundland also received transplants.

“Once somebody starts dialysis, they're on dialysis for life. They aren't able to come off of it unless they do receive a kidney transplant. Those are really the only two options because there is no cure for kidney disease right now,” MacIvor said.

There are currently 271 Atlantic Canadians waiting for a kidney transplant.

“That's why we encourage people to sign their donor cards so that it can provide for all those other patients that are on the wait list.”

In Nova Scotia, there are more than 730 people on dialysis.

Hereditary disease

Bourgeois discovered in the 1990s that his kidneys were failing. He was diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease, a genetic disorder where multiple cysts grow within the kidney, causing it to enlarge.

“As the cysts get bigger, the less your kidneys operate. Eventually, it just shuts down your kidneys because the cysts have taken over your kidneys,” said Bourgeois.

His wife said the renal specialist informed them last year that Bourgeois' kidneys are now the size of newborn infants — hence why his stomach appears extended.

The affected kidneys are usually not removed unless cancer is discovered. Kidney disease is not necessarily hereditary, but in Bourgeois' case, it was.

His two daughters were tested for the disease. Crystal Farrell, who also lives in New Minas, discovered at 19 years old that she had it and that her sister was likely a carrier.

“Dad is the first one in his family that we know of. There's probably quite a few carriers that we don't know of. But, Dad is the first one that presented with it,” said Farrell, who is married and, like her sister, doesn't have children.

“She's probably a carrier but she's not having any children so it's going to end with us.”

Can’t live without a kidney

Farrell said discovering she had the disease played heavily on her mind as a young woman, and after the initial shock, she began planning for the inevitable.

“Polycystic progresses. Your kidneys don't usually fail until your 40s,” she said.

“It literally affected every decision I made in my adult life because I had to be careful with how I treated my body. I also had to know that when I'm in my 40s, there's a really big chance that I'm not going to be able to work and that financially I'm going to have to be able to support myself,” Farrell said.

She worked in management roles as she built her career, with her last role being an assistant manager at Pete's Frootique in Wolfville.

Farrell said people often don't understand that kidney disease doesn't magically go away. A person cannot live without a kidney.

“There's not a lot of awareness about kidney problems and what that means,” said Farrell.

“When I first got sick and I had to stop working, I'd go into my work and people would say 'are you feeling better now?' There's this misconception that kidney problems are like the flu. You're not going to get better. The only way I'm going to get better is to get a transplant.”

Her family are big proponents of organ donation and hopes people will realize how much hope and life that one person can give if they sign a donor card.

“A transplant is really our only option. It's not a cure, but it's a treatment that will extend our lives and provide us with more freedom and health,” said Farrell.

This summer will mark Farrell's third year on dialysis. She's currently on peritoneal dialysis, meaning she treats herself at home.

“I do my treatment every day. It's a gentler type of dialysis but it's more of a time commitment,” she said, noting the system runs for 10-plus hours overnight.

She's hopeful a life-altering transplant will be in the cards in the near future. Statistics show Nova Scotians usually wait, on average, two-and-a-half years for a transplant.

In the meantime, she's carrying on with her rigorous daily treatments and trying to meet the necessary qualifications for a transplant.

“I'm lucky that I don't have to worry about (travelling for hemodialysis)... right now because I'm at home, but I have been told that I will have to go back to hemodialysis in the future, and then that's going to be another big worry,” she said, adding that she hopes Kentville's facility will be open by then.

“They didn't give me a time frame but they told me it was inevitable. Peritoneal can only work for so long,” said Farrell.

Did you know?

To sign up for organ donation, call MSI toll-free at 1-800-563-8880 or visit: www.legacyoflife.ns.ca.