KENTVILLE, NS - There’s no question that successfully completing the Court Monitored Mental Health Program (CMMHP) can be a cathartic moment for participants and program team members alike.

Nova Scotia Legal Aid lawyer Chrystal MacAulay said her job in the CMMHP is duty counsel, representing participants in court. Although it isn’t a requirement, she is usually the lawyer who represents CMMHP participants.

She assists clients with initial applications and a consent and waiver form that has to be signed before someone can be accepted into the program. The form establishes the facts about what happened, allows participants to accept responsibility for their offences and outlines what is expected of them and what he or she can expect in return.

Unlike traditional court, there is no set time limit for a participant’s involvement. Being involved in the program will purposefully increase the number of court appearances but there is a legal benefit for participants at the end.

“It’s a program I’m really proud to be involved with, quite frankly,” MacAulay said. “I think it’s really needed, not only in this community, but in Nova Scotia and Canada in general.”

She said it’s “quite humbling” to be able to help someone on their journey to mental wellness.

‘It has had a real mark on them’

Participants in the program have come in contact with the law because of mental illness or mental health issues. In her opinion, the traditional criminal justice system is not equipped to effectively handle most people who are struggling with mental illness.

“This is really a good alternative, not only for my clients, but for the community,” MacAulay said.

In her opinion, if participants can be set up with individual treatment plans and follow them, the treatment plan becomes entrenched and becomes routine. This will decrease the likelihood of participants offending again down the road because the root problem has been treated.

Going through the traditional criminal justice system is not nearly as intensive and doesn’t require as much effort as the CMMHP does, she adds.

There’s another benefit as well: the sense of pride and accomplishment for the participants who successfully complete the program, she says. A ceremony is held in the courtroom where the judge comes down off the bench and presents the graduate with a certificate and shakes the graduate’s hand. The program team always makes sure to have a cake to mark the special occasion. Graduates usually invite family and friends to share in the celebration.

“You can definitely see it with each individual client, it has had a real mark on them for sure,” MacAulay said.

All participants have to sign the consent and waiver form but most don’t have to enter a formal guilty plea to be accepted into the program.

There have been participants who have had to plead guilty as a condition of entry but MacAulay said this is usually a reflection of the seriousness of the charges and the circumstances behind the charges. Case-by-case analysis determines this and it’s usually a Crown decision whether or not a guilty plea is required.

Read more from the Court Monitored Mental Health Program series:

• Kings North MLA’s experience leads to advocating for province-wide mental health court access

About the program

According to publicly available information, the main goals of the CMMHP are to improve well-being and living situations for people living with mental illness who are in conflict with the law in order to decrease the likelihood of these individuals committing more criminal offences. The program also prominently weighs the potential risk or harm to the public in all decisions.

The CMMHP currently sits every second Wednesday at the Kentville Justice Centre, with the next sitting Feb. 21.

The program is not a trial court. However, in the opinion of the Crown attorney, there must be a realistic prospect of conviction should the matter proceed to trial. The Criminal Code requires the consent of the Attorney General for an individual to be accepted into the program. This consent is determined by the local Crown attorney.

To be eligible for the program, a person must be an adult age 18 or over charged with a criminal offence within the jurisdiction of Kings and/or West Hants counties. The participant must also reside in Kings or West Hants.

The participant must have a mental illness that is connected in some way to the alleged offence or offences. For eligibility purposes, a “mental illness” means a recognized, significant and persistent mental illness such as schizophrenia, mood disorder, bipolar disorder, other psychosis, major depression or co-occurring mental health and substance-related dependency where the mental illness is the primary concern.

Program participation is voluntary. Candidates must sign consent forms for release of details pertaining to his or her mental health, treatment, substance use, legal status and history so that this information can be shared with the program team.

Once screenings are completed and all relevant information gathered, the program team will decide if the candidate meets eligibility requirements. The program team makes the final decision on whether or not to invite an applicant to participate. If a participant decides to leave the program, his or her case will be returned to the court of origin.

If a candidate is accepted into the program, an individualized support plan is developed. Agreed to by the participant, the support plan could include requirements such as participating in programming and attending clinical appointments.

If a participant fails to comply with his or her support plan, efforts will be made to work with the participant to help ensure success. Cooperation is very important; if cooperation isn’t evident, the program team may make recommendations to the judge to impose special conditions known as sanctions.

Sanctions will depend on the participant and could include an increase in court appearances, closer supervision, changes to release conditions, revisions to support plans and removal from the program.

The four phases of the program include the appearance phase, the screening phase, the support plan development phase and the program phase.

On completion of the program, outcomes could include charges being withdrawn, an absolute discharge, a conditional discharge, a fine, a peace bond, a conditional sentence, probation, community service or detention.

Collaborative effort

The CMMHP was founded on partnerships involving the Kentville Justice Centre, the Nova Scotia Public Prosecution Service, Nova Scotia Legal Aid, Community Corrections and Mental Health and Addiction Services of the Nova Scotia Health Authority. The program falls under the jurisdiction of the provincial court and a provincial court judge presides over the program.

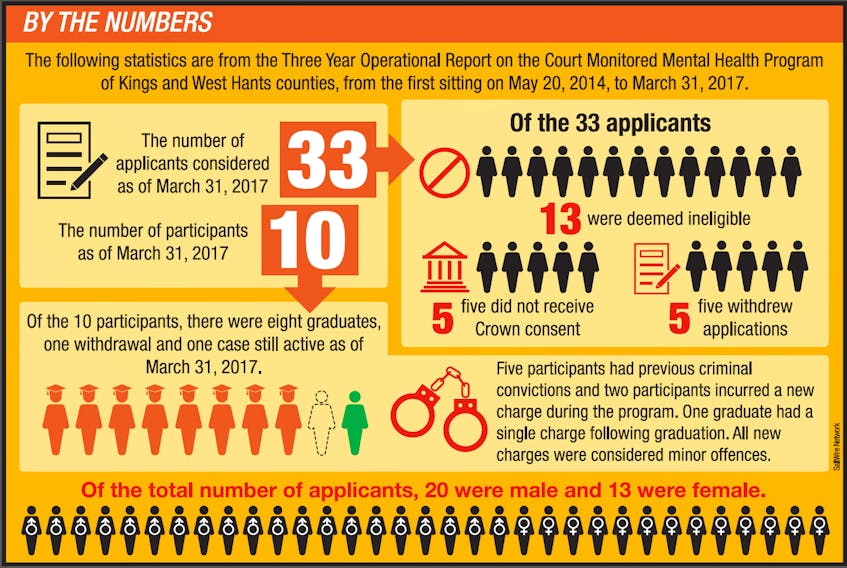

According to the CMMHP Three Year Operational Report, the program uses existing community supports. The collaboration of key stakeholders has resulted in a more effective and efficient model of service delivery with no added funding except the in-kind contributions and commitment of each stakeholder.

Representatives of the police, justice and health systems had been coming together since 2007 to find ways to collaborate and coordinate services to improve the response to people living with mental illness and addictions. Initial partnerships focused on emergency response but in 2013 attention was turned to the need for a mental health court model.

Key stakeholders came together to discuss how a court monitored program might be established in the absence of new funding. The CMMHP was launched in May 2014.

As pointed out in the report, it has been recognized that program eligibility criteria need some refining. Eligibility criteria during the pilot phase of the program were narrow. This allowed the program to start without an overwhelming number of applicants and to learn to work effectively together with lower risk cases.

There was some confusion around which diagnoses the team was accepting to screen for a nexus. This remains under consideration as the team is looking at expanding and reviewing what mental health services are available to provide the treatment portion of the program. The team is also considering the inclusion of applicants who reside elsewhere or have charges elsewhere but have a strong link to Kings or West Hants counties, such as treatment providers or school.

The following responses are from a participant survey for CMMHP graduates:

- “I am sleeping much better now.”

- “My thinking is better than it used to be.”

- “I am encouraged to continue with my mental health treatment.”

- “I have better control of my drinking and-or drug use.”

- “I am able to control my anger much better now.”

- “I have a positive relationship with my family and friends.”

- “I do not do activities that get me in trouble with the law.”

- “I am connected with services I need in the community (e.g. housing, employment, education, etc.).”